Critical reflections on calls to set an extra place at Passover Seders for Israeli hostages held in Gaza

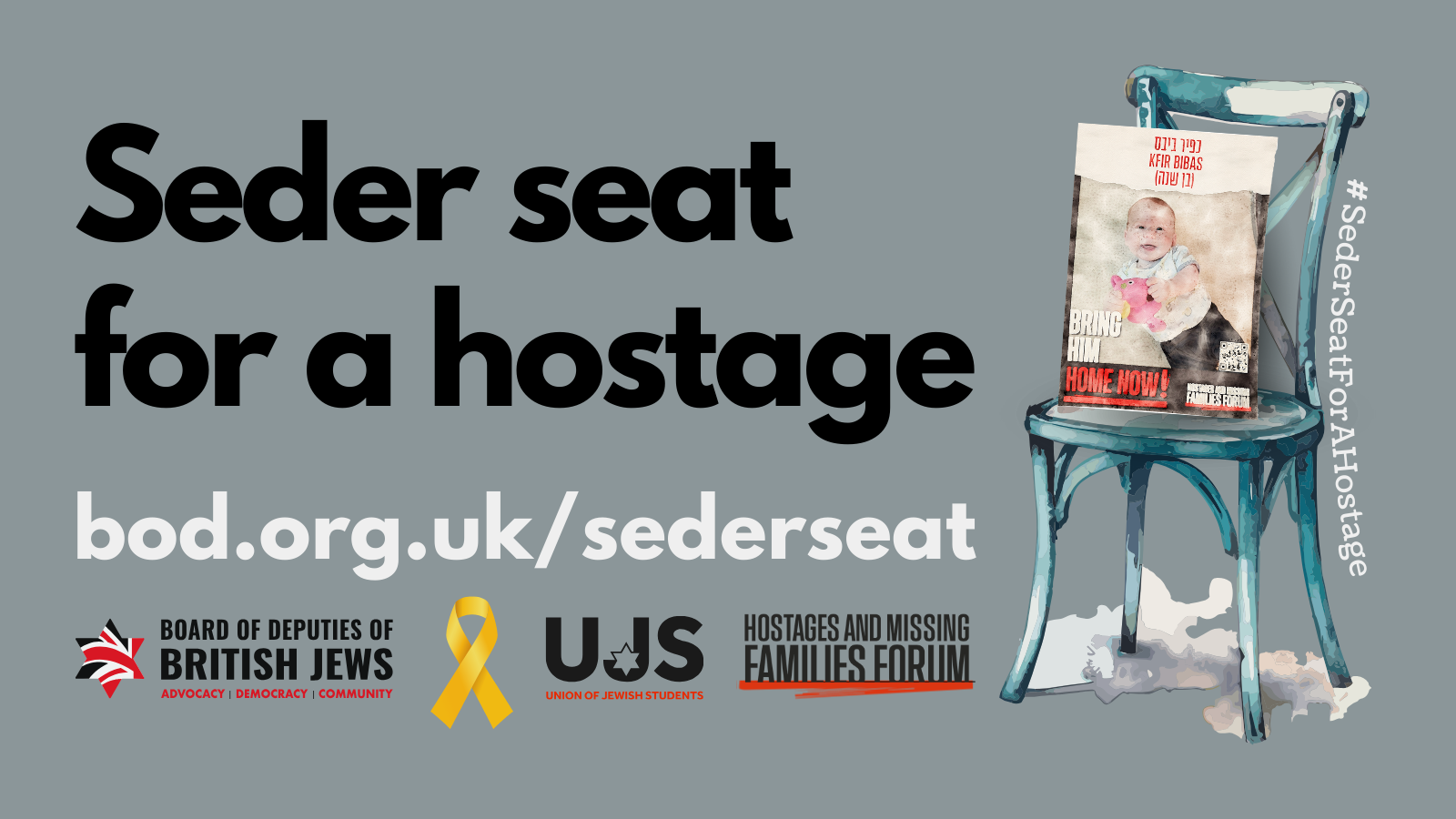

There has been a widespread call this Passover for Jewish families to take an extra action at their seders; to create an ‘empty seat’ for one of the Israeli hostages still held in Gaza. For several months now, synagogues have been doing this each week at Shabbat services, and now the campaign has been extended to Pesach, with the Board of Deputies urging ‘individuals and families to set an extra place at their seder table for one of the more than 100 men, women and children still held captive by Hamas.’

Made to be shared, this is a campaign built for the social media era, and the Board has asked people to ‘share pictures of their laid Seder Table with the seat set aside for a chosen hostage, along with the #SederSeatForAHostage hashtag.’

I want to examine this campaign from a few different angles: historical, political and religious. First the historical; the idea of using empty chairs at a seder is not new – it originated in the 1960s. Looking through a few archives, the only earlier precedent I can find is a Jewish Telegraph Agency (JTA) article from 1945 which suggests that some American Jewish families placed an empty chair at their seder in connection with family members who were serving abroad in the US military. This probably related to wider, non-Jewish rituals around war service and memorial. But the idea rose to prominence around what become known as the ‘Soviet Jewry Campaign’ – a campaign for Jews in the Soviet Union to be allowed to emigrate, ideally to Israel. This was a huge campaign, lasting around 25 years, which would do a great deal to shape diaspora Jewish identity in the post-WW2 era, and whose influence is insufficiently recognised today. The campaign had a strong connection to Passover, and to the Exodus narrative more genuinely – its famous slogan was ‘Let My People Go’. The first archival mention I’ve found is from the Jewish Chronicle from 1964 when the Israeli organisation Maoz, representing Russian Jews who had emigrated to Israel, issued a call for Israelis to leave ‘one chair vacant’ at their seders that year. Maoz said that the empty chair ‘should symbolise hope for an eventual exodus of the Jews in the Soviet Union and also serve as a silent protest against their present sufferings.’ From these beginnings the campaign mushroomed, becoming widespread in the 1970s and 1980s, alongside other rituals like Bar mitzvah boys’ ceremonies being ‘twinned’ with those in Russia who were prevented from having one. Sometimes individual Soviet Jews were named as part of the campaign; in 1972 the Association of Jewish Women’s Organisations asked synagogues holding communal seders to ‘adopt’ one of 20 Soviet Jewish prisoners, saying ‘Each Seder will have an empty chair, with a large photograph of the prisoner, and the officiant at the Seder will inform the guests of the prisoner’s case-history.’ The custom had its heyday in the 1970s, decreased in the 1980s, and fell into abeyance with the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. The current campaign has not officially connected itself to this history, presenting itself as an innovative response to the current situation, but the explicit echoes are unmistakeable.

Secondly, I want to look at the politics of this campaign. Who is it directed at? Perhaps they organisers believe the demand to ‘bring them home’ is directed at Hamas, who, they believe, should release the hostages unconditionally. It seems unlikely, however that Hamas is likely to be swayed by actions taken at seder tables. More likely is that it’s aimed at Western governments and wider public opinion; to keep the hostages in public awareness, and thus promote the idea that Israel’s war in Gaza is just, because it seeks to bring the hostages home. The argument seeks permission for Israel to continue the war, to resist demands for an immediate ceasefire and for the West to continue arms sales to Israel – the hostages are the justification for all of these. The trouble with this argument is that it is easily refuted by reference to the actions of the Israeli government and reveals a major difference between Israeli and Jewish diaspora discourses right now. In Israel, to focus squarely on the hostages is an anti-war stance. Those protesting on the hostages’ behalf, led by the families of those held captive, are calling for a ceasefire and a negotiated exchange of hostages for Palestinian prisoners held by Israel. In many cases they have been demanding an ‘all for all’ deal – all the hostages in exchange for all Palestinian prisoners held by Israel. These number in the region of 10,000 people, many of whom have never been tried. While the prisoner exchange is the focus, there is widespread understanding amongst the movement in Israel that a ceasefire is the prerequisite for any such exchange. This is because many of these Israelis recognise a simple truth; that Israel has the power to bring the hostages home and has had that power since October 7th. Very soon after October 7th Hamas made it clear that it was open to an exchange, and one was actualised in November 2023, which led to the freeing of 105 hostages and the release of 240 Palestinian prisoners. Israel managed to free two more hostages militarily but killed several more in botched operations. Attempts to free them through force have failed, whilst freeing them through negotiations proved remarkably successful. The precise numbers and timing would have to be negotiated, but the basis for such a deal, as mediated by Egypt and Qatar, has existed for months.

Why hasn’t this happened? The answer is that the war isn’t just about the hostages. The Israeli government seeks also to destroy Hamas, in revenge for October 7th, and refuses to fully evacuate its army from Gaza. Such an evacuation, alongside allowing Palestinians from the North of the Gaza Strip (including Gaza City) to return is a prerequisite for an agreement. Because of the goal of wiping out Hamas – which is arguably impossible, even if it was possible to destroy its military capabilities – the Israeli government doesn’t focus so much on the hostages. It instead talks about October 7th, about reinstating security, about creating the conditions that would prevent such a massacre ever reoccurring. It seems like Benjamin Netanyahu is willing to sacrifice the hostages for the sake of continuing to fight Hamas and to ensure his own political survival. As soon as the war ends, and the hostages who are still alive are brought home, Netanyahu is likely to be out of office and back on trial for corruption. So he has an impetus to prolong the war, and not agree a ceasefire / exchange deal that would #bringthemhome.

We have then a strange disconnect between Israel and diaspora: in Israel to focus on the hostages is a pro-ceasefire position; in the diaspora it represents a call to continue the war. Simply bringing attention to this disconnect is worthwhile – ‘standing with Israel’ is not a straightforward matter when there are such divergent views within Israel. And I think it’s also worthwhile for those of us who are connected to the Palestinian solidarity movement to do more to talk there about the hostages. Not to support the war but to call for its end, and for the hostages’ liberation alongside the liberation of the people of Gaza. In terms of this specific campaign, I think it would be a mistake to oppose it. Just as those who tore down or defaced the now-ubiquitous posters of hostages were falling into a political trap, for Jews who support a ceasefire to speak against the ‘empty chair’ campaign would be to accept the false logic that caring about Palestinian suffering and the suffering of the hostages are mutually exclusive. Rather we should seek to expand the campaign: we should call for more empty chairs to be laid – chairs for Palestinians killed in Gaza, especially the approximately 14,000 children. At its best, the ‘chairs for hostages’ campaign tries to bring attention to an absence, to people who we wish were with their families but cannot be. There is so much absence in Gaza, so many families who have lost children, parents and siblings; let us remind ourselves of them too. Let us make space for more chairs.

Finally, I want to consider the religious aspect of this campaign. It is calling for a change not just in Jewish secular culture but for an alteration in religious ritual. There are a couple of precedents that make the change appear to grow organically out of Jewish tradition. They have to do with the prophet Elijah who, according to tradition, will return to announce the imminent arrival of the messiah. There is the custom of leaving an empty chair at a circumcision for Eliyahu – the ???? ?? ????? – designed so that Elijah will protect the baby from harm during the ceremony. And at the seder there are two traditions, to open the door for Elijah to enter near the end of the Seder, and to fill an extra cup of wine for Elijah to drink. In my family seders we would leave the door open, and watch Elijah’s cup with excitement, giddily pronouncing that we had seen the wine level go down, before ‘ushering him out’. There was the thrilling possibility that someone might be outside the house at that exact moment we opened the door and thus we would inevitably invite the baffled individual to come inside. As well as announcing the coming of the messiah, Elijah’s role in the tradition is rule on legal questions on which rabbis cannot agree. The rabbinic word for an unsolved question – is ???? (teiku), which means let it stand, but is sometimes explained as being an acronym for ???? ???? ?????? ?????? – the Tishbite [Elijah] will answer questions and problems. At the seder the tradition is to drink four cups of wine, but there is a minority view expressed in the Talmud that it should in fact be five. To honour both positions the Rambam (Maimonides) ruled that a fifth cup should be poured and not drink and somewhere down the line this became connected with the idea that one day Elijah would rule on whether it should be four cups or five, hence it became Elijah’s cup.

What these elements have in common is that Elijah – and the object dedicated to him – represents the messianic future, something yet to come, out of reach. Something so perfect it necessarily cannot be of the present. The traditional 4 cups are associated with 4 past promises made by God that have (according to Exodus 6) been fulfilled: I will free you; I will deliver you; I will redeem you; and I will take you to be my people. But the disputed fifth cup is connected to a promise that is not due to be fulfilled until the messianic age – I will bring you into the land which I swore to give to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. This is the source of much controversy – is the Biblical promise that Jews will be restored to the promised land one that will come through divine action, at the end of days, or can it be ‘forced’ by human action? The former was the mainstream religious position for almost all Jewish history, the latter a modern rethinking by the secular Zionist movement who believed it time to take things into their own hands. Rabbi Israel Abraham Kook, a key founder of religious Zionism, gave a eulogy for Theodor Herzl in 1904 and described Herzl’s secular Zionist movement as being the ‘footsteps of the messiah son of Joseph’ (the first messiah who is said to precede the arrival of the messiah son of David), thus imbuing the whole movement with messianic characteristics. Just as the future messianic promise of return has been turned into a real-life state-building project, seder rituals concerned with the intangible future have become literalised, to focus attention on very real hostages. The ideal has been sacrificed in service of the political.

I think we need to be concerned about this. It is part of the shrinking of Judaism, from a religion with universal themes and concern for humanity in general, to a narrow peoplehood cult, in which the losses and gains of our ethno-cultural group are the only things that count. The liberation of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery should not be read narrowly and paralleled only with the imprisonment or freedom of contemporary Jews. Our Passovers need to be concerned with all instances of slavery and celebrate all who have gained their rights, looking forward to a messianic era when all are liberated. The campaign to place pictures of hostages is part of the ongoing project to nationalise Judaism, to interpret ‘let my people’ go as ‘set free all captive Israelis and Jews’. Of course, I hope that the hostages are released, immediately. But we need to hope for more than that. In the words of the Jewish-American poet Emma Lazarus, writing in 1883: ‘Until we are all free, we are none of us free’

.