What a British Jewish politician from 100 years ago can teach us about anti-Zionism and antisemitism

This is the 6th Torat Albion essay. It has a more historical bent to the others and relates to my academic research more closely. Thank you for subscribing or reading, and I hope you’re enjoying the journey. I’d love this to feel like a community of enquiry rather than just a top-down initiative, so please do post your thoughts as comments or send them to me by email. If I can, I’ll incorporate your thoughts into future pieces. At some point I hope to create a Torat Albion podcast, to discuss the issues in the week’s essay with some guests, thus furthering the dialogue. And do share the posts with others who you think might be interested.

Things to read (I don’t necessarily agree with everything in them):

A rich piece on the history of the Venetian ghetto in the LRB.

A provocative but enlightening piece on philosemitism and the White House by Em Cohen

A fascinating read from August 2023 on Israel’s bizarre futurist neo-liberal plans for rail lines across the middle east

A detailed overview of developments within the anti-antisemitism movement over the past 15 years from Adam Sutcliffe

A thought-provoking collection of essays from 2022 on Palestinians imagining futures beyond the model of the nation state (free book)

By now, most people are aware that Jewish non, or anti-Zionism exists. The numbers of such people attending the regular Palestinian solidarity demonstrations has become too large to ignore. When it comes to the history of Jewish non/anti-Zionism, most people think of two distinct groups. Firstly, there’s Neturei Karta, a spin-off from the orthodox Agudat Yisrael movement which was founded in the late 1930s in Jerusalem. Their ubiquitousness at Palestine demos has made them wildly popular amongst non-Jews who wish to state that Judaism is not synonymous with Zionism (it’s not, but it’s complicated). The other group is more obviously historic, the Jewish Labour Bund, the revolutionary Jewish socialist organisation founded in Russia in 1897 who helped founded the Social Democratic Labour Party which would eventually lead the Russian Revolution, and who would later flourish in inter-war Polish. Again, most activists are drawn to the Bund for its fierce anti-Zionist rhetoric, although its anti-Zionism was very different to contemporary forms, founded on the lack of realism involved in the idea that millions of Jews from Eastern Europe would move to Palestine and be able to support themselves there. But there is a third group which receives far less attention, and even shorter shrift: the assimilationist anti-Zionists of Western Europe and the United States.

The Jews of Western Europe gained emancipation in the 18th and 19th centuries by loudly proclaiming the patriotism and loyalty to whichever country they lived in. This became known as the ‘emancipation contract’; Jews could have rights, like the right to vote, stand in parliament or take on certain position, as long as the rejected other loyalties, to the countries from which they had emigrated, and to Jews in other countries. Their Jewishness was to become strictly a matter of religion, a creed which one expressed purely in the home or in synagogue, whilst being patriotic nationals in public. Hence the UK expression: Englishmen of the Mosaic Persuasion, which put Englishness front and centre and limited Judaism to a persuasion, a matter of taste (and of course the slogan completely overlooked Jewish women, or indeed Jews living in Scotland, Wales and Ireland).

It’s hard to appreciate it now but such Jews represented the mainstream and the vast majority of the Jewish community in Western Europe and the US; the idea that Judaism was anything other than a religion remained a fringe one before the late 19th century. The designation ‘assimilationist’ was one coined by their opponents, by political Zionists, after the movement was founded in 1897. It sought to label them as not ‘proper Jews’, Jews who simply wanted to assimilate into the population in which they lived. But assimilation and intermarriage were becoming increasingly easy, and those who wanted to give up being Jewish could increasingly do so. Those who remained as Jews but articulated a form of Jewishness in opposition to Zionism did so because they wanted to, and because they believed that their form of Judaism was the correct one. They were maintaining the Judaism of their parents and grandparents, against the upstart Zionists who sought to radically change its terms. Zionists viewed Jews a race (though it would later come to be softened into ‘a people’) who needed to leave the countries in which they lived to form their own society, on whatever piece of land they might be able to obtain from the imperial powers of the time.

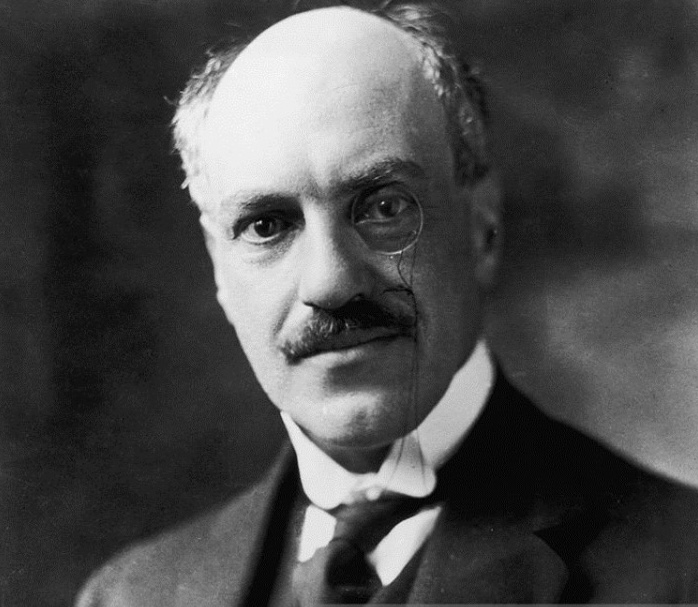

Edwin Montagu was a particularly interesting member of the assimilationist group. Despite being one of the earliest British Jewish cabinet ministers, and Secretary of State for India 1917-1922, he is surprisingly little known. Montagu was more knowledgeable of Judaism than many assimilationists, having grown up in an Orthodox home, the son of Liberal MP and businessman Samuel Montagu. It’s true that as an adult Montagu had little interest in practicing Judaism, unlike his sister Lily, one of the founders of Liberal Judaism. But he had a firm upbringing it, attended synagogue regularly, and was even sent on a madcap world tour at the age of 12, accompanied by his Hebrew teacher who was employed to make sure the young Edwin observed shabbat and kashrut during his travels. Letters written while at university in the early 1900s show Montagu rejecting his father’s entreaties for him to attend the local synagogue whilst stating:

By race I am an Englishman and my interests are mainly in England but I will never forget that I am a “Jew” and the son of a Jew and I will always be a good Jew according to my sights…I will never disguise my Jewishness or be ashamed of it (for why should I), but I must leave its ceremonial ritual and law excellent in their own way but not parts of a religion.

It was an accident of history that led to Montagu being the only Jewish member of the cabinet in 1917, as Zionist campaigners sought to win official British government endorsement of their cause. While there were prominent Jewish supporters of the Zionist cause in government at the time, most notably Montagu’s cousin Herbert Samuel, Montagu was the only Jew at the top table, and he used that position to make his feeling known. In a string of memoranda, Montagu slammed the planned declaration, in the process making himself the most important Jewish anti-Zionist of his day.

Most anti-Zionism of the time was founded on concerns for how Jews in the rest of the world would be treated should Zionism succeed in its aims, rather than concern for rights of Palestinian Arabs, and Montagu was no exception, but he did make some far-sighted comments in this regard. In his first memo, Montagu wrote that the proposed Jewish national home implied that: ‘Mohammedans and Christians are to make way for the Jews, and that the Jews are to be put in all positions of preference…that Turks and other Mohammedans will be treated as foreigners…Perhaps citizenship must be granted only as a result of a religious test.’ It’s significant that Montagu spoke of ‘Mohammedans (i.e. Muslims) and Christians’ rather than of Arabs; consistent with his view of Jews, he saw groups in religious rather than racial terms.

Montagu also wrote that the concept of the Jewish national home would result in ‘a population in Palestine driving out its present inhabitants, taking all the best in the country’, and whilst accepting that Palestine played ‘a large part in Jewish history’, he suggested that it was also very significant in Muslim and Christian history. He stated that while he would not ‘deny to Jews in Palestine equal rights to colonisation with those who profess other religions’, he added that ‘a religious test of citizenship seems to me to be only admitted by those who take a bigoted and narrow view of one particular epoch of the history of Palestine, and claim for the Jews a position to which they are not entitled.’ In another memo Montagu asked rhetorically ‘is it conceivable by anyone who knows the country that there is room in Palestine for a large extension of the population? If this does not occur, what part of the existing population is it proposed to dispossess?’ In 1919, as secretary of state for India Montagu’s priority was to pacify world Muslim opinion to keep the peace in India. As such he urged the post-WW1 peace treaties not to abolish Muslim rule in the middle east, saying that Palestine ‘for over one thousand four hundred years has been Mohammedan and should not be given over to a non-Mohammedan government’.

Despite these points, the bulk of Montagu’s critique was that Zionism would lead Britain to discriminate against Jews, it would create the false image that Jews were not truly at home in Britain and create pressure that they should move to the middle east – ‘Jews will hereafter be treated as foreigners in every country but Palestine’. Montagu even made a theological claim, reminiscent of Neturei Karta, saying:

I have always understood, by the Jews before Zionism was invented, that to bring the Jews back to form a nation in the country from which they were dispersed would require Divine leadership. I have never heard it suggested, even by their most fervent admirers, that either Mr Balfour or Lord Rothschild would prove to be the Messiah.

This echo of the ‘Three Oaths’ from Talmud Ketubot 111a, key to most Jewish religious anti-Zionism, shows that Montagu had imbibed more traditional Judaism than his critics cared to admit.

The most striking aspect of Montagu’s critique, however, was that that Zionism, and British support for it, was in fact antisemitic. His initial memo was entitled ‘The Anti-Semitism of the Present Government’, and he immediately clarified that while he was not suggesting that the government was ‘deliberate anti-semitic’ but rather that ‘the policy of His Majesty’s Government is anti-Semitic in result and will prove a rallying ground for Anti-Semites in every country in the world.’ I think there are four distinct ways in which we can say that the Balfour declaration was antisemitic, not all of them arguments made by Montagu.

Firstly, the process which resulted in the declaration came about due to the government’s belief in antisemitic conspiracy theories. The government believed that Jewish world opinion and ‘Jewish finance’ could help them win the war; stop what they perceived as Jewish support for Germany and for the Russian Revolution (which led Russia to withdraw from the war); and convince the United States to enter the war on the allied side. This belief was not well founded; Jews certainly didn’t have the power to make any of things happen, but certain Zionist activists were not above using such beliefs to advance their cause, giving the impression that they did in fact hold such power. Secondly, there was a longstanding desire to reduce Eastern European Jewish immigration into Britain. This had been the motivation for passing the Aliens Act of 1905, a piece of structurally antisemitic legislation, passed while Balfour was Prime Minister. Zionist leaders such as Herzl had promoted various settlement schemes (such as to El Arish, in the Sinai desert, and to British East Africa) as means to reduce the Jewish immigrant population of Britain. The commonality between Zionists and antisemites in the period is illustrated by the antisemitic group The Britons who, in 1920, declared themselves ‘convinced Zionists’ who while ‘out to secure Britain for Britons’ were ‘no less out to secure Zion for Jews’, seeing possible schemes in ‘Palestine, Madagascar or Australia’ as ways for Britain to decrease its Jewish population. Thirdly, Zionism acted as a justification for countries not to fully emancipate, or to de-emancipate Jews, as it allowed them to say that Jews would rather find their fulfilment in a separate nation. As Montagu wrote:

when the Jew has a national home, surely it follows that the impetus to deprive us of the rights of British citizenship must be enormously increased. Palestine will become the world’s ghetto. Why should the Russian give the Jew equal rights? His national home is in Palestine. Why does Lord Rothschild attach so much importance to the difference between British and foreign Jews? All Jews will be foreign Jews, inhabitants of the great country of Palestine.

A final way in which the Balfour Declaration can be seen as antisemitic is in the way in rejected the entreaties of assimilationists (integrationists would be a more neutral term) like Montagu to be fully British. Ministers such as Balfour, Asquith and Lloyd George rejected the idea that Jews could be fully ‘of Britian’, seeing them as essentially Asiatic or semitic, and believing they were more loyal to each other than to Britain. They thus found Zionist race-thinking far more palatable and convincing than Montagu’s anglicised Judaism, as the latter would have implicitly required Britain to grant full equality and consider the British metropole as a multi-faith, multi-racial country. To use a contemporary term, it would have required it to be a state of all its citizens. Montagu wrote proudly that ‘More and more we [Jews] are educated in public schools and at the Universities, and take our part in the politics, in the Army, in the Civil Service, of our country’, but many non-Jewish ministers were not so sanguine about those developments, and preferred to advocate a future in which Jewish nationalism could allow English institutions to retain their racial and religious exclusivity. They preferred to consider British Jews as potential citizens of the new Jewish national home than ladies and gentlemen of the Mosaic persuasion.

Inevitably, Montagu lost. On 2nd November 1917, while Montagu was in India, Arthur Balfour sent his historic letter to Lord Rothschild, promising the Government’s support for ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people’ (an earlier draft had said ‘Jewish race’. Two additional clauses had been added to assuage the concerns Montagu had raised, with the text stating that ‘nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.’ As we know, the first promise was not kept. The rights of Palestinian Arabs were very much prejudiced by the process of Zionist settlement, which could not have proceeded without British colonial patronage. I wonder if the second promise was kept either. While the existence of the state of Israel has certainly made Zionism far more popular amongst Jews than it was in Edwin Montagu’s day, many antisemitic incidents have their roots in misplaced responses to Israel’s behaviour, and by the dangerous tendency to conflate Israel and the Jewish diaspora. It’s often said that the existence of Israel has kept Jews safe; I would suggest that it has often put us in danger.

I don’t wish to derive simplistic lessons from this historic portrait. Of course, Montagu was a figure of his time, an eccentric character, a liberal imperialist (albeit a reformer). But I hope his story can will help disturb the common assumption that it is only anti-Zionists who are suspected of antisemitism and Zionists who are free from it. The tendency for those who do not want many Jews in their own country to simultaneously offer support to Zionism is not a new one. And the creation of a fully pluralist societies, in which all religious and ethnic group have an equal stake in the state, remains an unfinished project in countries like Britain. It has been the desire to keep countries like Britain religiously and ethnically homogenous (without Jews and other minorities) that has resulted in the disastrous forms of ethno-nationalism that we’ve seen in countries like Israel. If we want to deal with the consequences of settler colonialism over there, we might have to consider the British antisemitism at home which helped cause it.